The Promise Doctrine

I first heard Jason Womack on a “Productivity Show” podcast in 2006, when he was still with the David Allen Company. Jason is one of my favorite thinkers on productivity, and “The Promise Doctrine”, which is co-authored with his father, is his long-awaited (by me, anyway) book on productivity. It brings a lot to the table and will make a fine complement to the productivity bookshelf of people who are already familiar with other productivity thinkers like David Allen (Getting Things Done), Tim Ferriss (The Four-Hour Workweek), and Steven Covey (The Seven Habits of Highly Successful People).

Before I dive into the book itself, a brief digression is in order. One of the most important principles in economics is that trade creates wealth. It allows us to specialize and to use our time and energy in ways that are more productive — i.e., that allow us to achieve more of our goals. The publication information is telling about the myth that trading with poorer people around the world will bankrupt Americans: “Conceived, written and designed in the United States of America. Printed in China.” International trade allows Americans to specialize in advanced thinking on personal productivity, and we’re all richer for it.

The short lesson in economics aside, the book’s central theme (unsurprisingly) deals with making good on your promises. Indeed, I was surprised (and humbled) to find myself quoted in the preface regarding the ideal for promise-making and promise-keeping: deliver more than what is asked for before the deadline. As devotees of organizational systems know, we have more options and opportunities today than anyone who has ever come before us. It’s a dizzying and wonderful time to be alive. Nonetheless, we have to constantly adapt our organizational systems to these changing possibilities and opportunities.

The book begins with a Foreword by author Marshall Goldsmith, who points out that good promise-making and promise-keeping is an important part of good business ethics. The ability to make wise promises like this is a skill that can be learned from practice, repetition, failure, and reassessment. Is it easy to say “yes” to every request? It is. But it isn’t wise.

The Promise Doctrine is a quick read that isn’t designed to be read, ingested, and discarded. It’s essentially a workbook. There are regular exercises and assessments throughout, and it coaches the reader through various steps along the way with lots of white space, bold headings, and offset questions and statements that make it easy to skim.

Their “one central principle” is simple to remember but deceptively difficult to practice: “Do what you’re going to do, when you say you’re going to do it” (p. 11). They express this in a specific practice on page 13: “Make important promises, and keep them.” Once again, it’s easy to say and very hard to do. Often, we get ourselves in trouble when we make short-run concessions with long-run consequences we don’t fully appreciate. I, for one, do this far too often, and I would suspect that if you’re reading this you do the same.

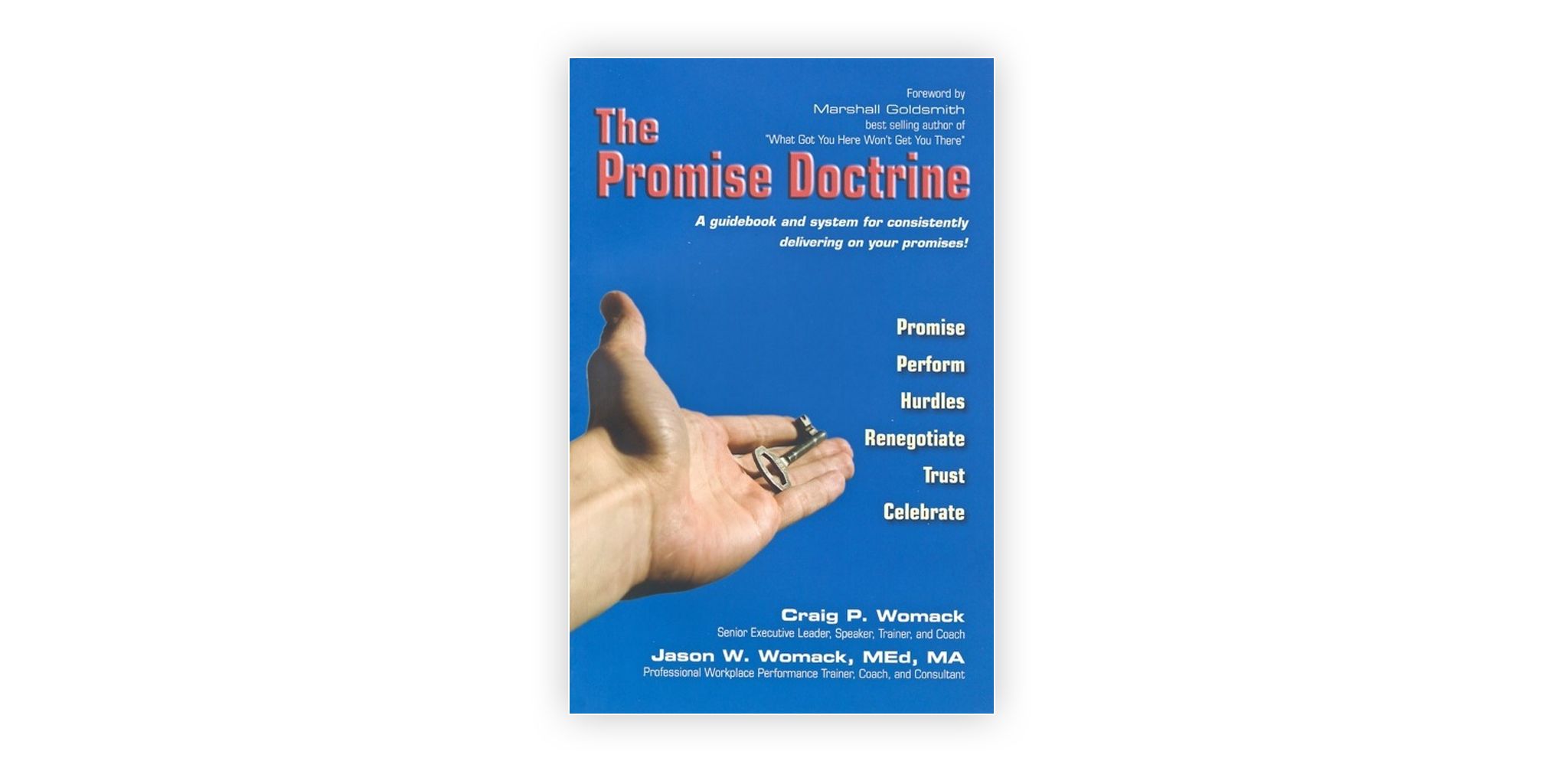

Exercises and implementation begin in earnest in chapter 3 and an instruction on p. 17 to “carry this book with you for at least the next 14 days” because “every page of ‘The Promise Doctrine’ provides tools, prompts, and guides that clear the path for promise making and promise keeping.” They make good on the promise, as the rest of the book consists mostly of exercises and “The Six Elements of the Promise Doctrine” (promise, perform, hurdles, renegotiate, trust, celebrate) and then fold-out pages discussing each of these elements.

The fold-out pages are especially interesting in terms of book formatting, but they capture the essentials of what they are trying to communicate about each element in single (large) pages. Design-wise, I found these a little difficult to handle (the stiff foldouts in the latter part of the book make it difficult to thumb through from front to back).

Reflect for a moment on how much more productive you and the organizations with which you interact could be if there were a near-certain expectation that what people (including you) promised would be delivered on time, every time. I’m sure you would be much more productive and likely much happier. You wouldn’t bind yourself up in unproductive commitments and relationship-damaging, or trust-eroding strings of broken promises. Craig and Jason Womack offer a simple handbook that can help you avoid this through well-managed commitments.